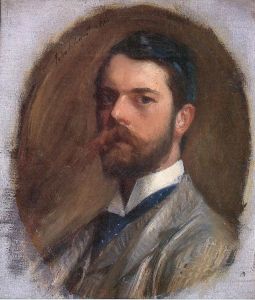

I went to the John Singer Sargent exhibition on Wednesday, at the National Portrait Gallery. It’s called Sargent: Portraits of Artists and Friends and attempts to represent a more “intimate, idiosyncratic and experimental” version of Sargent’s painting. The selection is based on portraits he did that were of his friends and social circle rather than those portraits that were commissioned from him.

It’s worth saying that the exhibition is very popular, so plan for that if you attend. Even on a Wednesday there was an hour wait from buying a ticket to being allowed in and once inside, it was very crowded. I found that quite surprising, given the relatively expensive cost of entry, £15 and Sargent, I would have thought, not being a huge “name” for most people. Anyway, for £15 you get a free little booklet describing each of the pictures, which comes in surprisingly handy since it’s difficult to get anywhere close enough to a picture to read a wall caption! Frustratingly, a lot of people seemed to want to stand in front of the pictures for minutes at a time, without actually looking at them, just to read their booklet. After finishing their reading, and a fleeting glance up for a couple of seconds to look at the actual work, they moved on to the next picture, to do the same again. Why would you take time looking at the book rather than the pictures? Difficult to understand.

Setting the physical experience aside, I found the exhibition very interesting. Although I’ve seen a few of his works up close, I knew very little about Sargent and the exhibition (and the background reading…undertaken before!) proved very informative. I had imagined him as spending most of his time in Boston, painting wealthy Americans, but in fact he spent his early career in Paris, his later career split between London, Boston and New York and, during the mid-1880s, spent a couple of years in Broadway. In the Cotswolds, of all places! Possibly I found this last fact more interesting than it deserves because I live close to this area myself, but I don’t think many people would automatically place Sargent as working in Broadway.

One reason he spent time working there was that he was part of a social set linked to an artistic community based there. That community of artists and writers was centred around the Millets, Frank (an artist) and Lily, and Sargent was devoted to these two. He painted many pictures of them, their house, garden and children culminating in one of his masterpieces, Carnation, Lily, Lily, Rose. He used their daughter, Katherine, as an early model for this picture. It’s very Renoir-like and highlights how much Sargent’s work follows in the steps of the Impressionists. Throughout the works on show there are impressionist influences, even one portrait of Monet which is, apparently, the only picture which shows him working in the impressionist method, en plein air. The exhibition’s later works, in particular, are very pretty and sun-dappled and easily mistaken for impressionist work.

This social set in Broadway that Sargent fell in with, and his wider social circle were quite Bohemian. Certainly they were not staid but Sargent himself was regarded as being very reserved, despite his social connections. There is, of course, the possibility that he was conflicted in some way about his sexuality, which exhibited itself as this reticence. He was a lifelong bachelor and may possibly have been trying to keep a lid on his nature in some way. An excellent article on the possibility of Sargent being gay can be found here. Whether he was or was not, he certainly mixed in circles with prominent, sexually ambiguous figures, including people like Oscar Wilde and Vernon Lee.

One of the more outrageous of these sexually ambiguous figures was Mabel Batten, the subject of the painting, Mrs George Batten Singing of 1897. She took many lovers of both sexes, including the Prince of Wales! Eventually, she ended her days in a lesbian relationship with Radclyffe Hall. The painting is one of the highlights of the exhibition for me. The brushwork outside of the face is very free, and the portrait captures her very dramatically, clearly representing her sensual, passionate personality.

Another woman with a scandalous background depicted in the exhibition is Ellen Terry, the actress. Terry was married to the Pre-Raphaelite artist George Frederick Watts when he was 46 and she was just 16. They separated after only a year, and she went on to have many relationships and 2 further marriages. The picture of Ellen Terry as Lady Macbeth is another highlight of the exhibition. The colours in the picture are amazing, the blues and greens of the dress and the red of her hair, in particular. The brushwork in the dress is incredible and the colours turn almost abstract if you look at it long enough. The pose is fittingly dramatic, like a living statue, and the piercing eyes are at the centre of the composition, drawing you in. There are Pre-Raphaelite influences and even a proto-Art Nouveau element in the elongated body. The arts and crafts, celtic patterned frame for the picture is fantastic, too.

These portraits of passionate, confident women, make me recognise that Sargent seems to treat men and women very differently in his pictures. The men all seem much more staid, more po-faced while the women seem more relaxed. Thsi could be just a reflection of Victorian society, I suppose, with the men wanting to be seen as stiff upper-lipped. Or perhaps it’s as though Sargent understands the women more, or is more interested in them than he is the men. Look at La Carmencita, with her amused face or Lily, Mrs Frank Millet, determined and knowing. One can imagine her sharing Sargent’s secrets, him confiding in her.

Perhaps the one man where this distinction does not quite apply is in Sargent’s portraits of the author, Robert Louis Stevenson. There are two portraits in the exhibition, the first of Stevenson and his wife, Fanny and the second of just Stevenson. In the first painting from 1885, Stevenson is not stiff but rather pacing nervously, a finger raised to his face. Thinking, pondering, he stares out at the artist (and the viewer). The eye, however, is drawn to his wife in her gold looking dress, even though she is at the edge of the frame and cut off. We sense a strong, perhaps controlling, female personality (as she was, apparently, in life). In the second painting from 1887, Stevenson on his own appears much more relaxed, even mischievous or louche. Given that Stevenson’s novel Doctor Jekyll and Mister Hyde was published in 1886, right in between these two paintings, it’s tempting to see the early picture showing Stevenson as Jekyll and the later Stevenson as Hyde. Possibly that may be reading a little too much into the works!

An interesting aspect of the composition of the earlier Stevenson picture is the separation of the two figures, the distance between them. When you notice this and start looking at other pictures in the exhibition, you see this is a common theme. Many pictures show just two figures, often separated either by distance or by one figure turning away from the other. In La Verre de Porto we see a very similar composition to the Stevenson picture, the main figure with a partner at the side who has been chopped off. Walking around, every other picture seems to be of just two people, separated in some way, and this continues even into the later works, where we see it in In The Garden, Corfu. Could this repetitive theme be Sargent commenting subtly on the state of the relationships around him? Or some indication bubbling to the surface, a yearning for a relationship of his own? Is he comforting himself that those relationships he sees around him are not perfect?

At the end of the exhibition, looking back, I realise I have spent a lot time looking for an interpretation of Sargent’s character through the paintings on show. Sargent’s personality is elusive in his work and I found myself looking for hints of suppressed sexuality, of duality and the hidden, closeted, seething underworld of Victorian society. I especially expected to see these elements because the focus of the exhibition is portraits of his friends and you would, therefore, expect a certain relaxation from Sargent around them. You can find a few of these elements if you look hard enough, as I’ve outlined above. On the whole, though, I have to be honest and say that, really, there isn’t that much evidence for repression or darkness in the bulk of the works on display. They are, with a few exceptions, what I think you would expect from a Sargent exhibition – extremely accomplished but, ultimately, superficial society portraits.